Immune System SeriesT Cells and Lymphokines

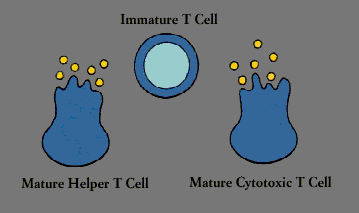

T cells contribute to the immune defenses in two major ways. Regulatory T cells are vital to orchestrating the elaborate system. (B cells, for instance, cannot make antibody against most substances without T cell help). Cytotoxic T cells, on the other hand, directly attack body cells that are infected or malignant.

Chief among the regulatory T cells are "helper/inducer" cells. Typically identifiable by the T4 cell marker, helper T cells are essential for activating B cells and other T cells as well as natural killer cells and macrophages. Another subset of T cells acts to turn off or "suppress" these cells.

Cytotoxic T cells, which usually carry the T8 marker, are killer cells. In addition to ridding the body of cells that have been infected by viruses or transformed by cancer, they are responsible for the rejection of tissue and organ grafts. (Although suppressor/ cytotoxic T cells are often called T8 cells, in reality the two are not always synonymous. The T8 molecule, like the T4 molecule, determines which MHC molecule-class I or class II-the T cell will recognize, but not how the T cell will behave.)

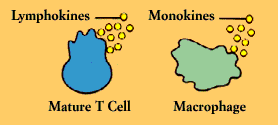

T cells work primarily by secreting substances known as cytokines or, more specifically, lymphokines. Lymphokines (which are also secreted by B cells) and their relatives, the monokines produced by monocytes and macrophages, are diverse and potent chemical messengers. Binding to specific receptors on target cells, lymphokines call into play many other cells and substances, including the elements of the inflammatory response. They encourage cell growth, promote cell activation, direct cellular traffic, destroy target cells, and incite macrophages. A single cytokine may have many functions; conversely, several different cytokines may be able to produce the same effect.

One of the first cytokines to be discovered was interferon. Produced by T cells and macrophages (as well as by cells outside the immune system), interferons are a family of proteins with antiviral properties. Interferon from immune cells, known as immune interferon or gamma interferon, activates macrophages. Two other cytokines, closely related to one another, are lymphotoxin (from lymphocytes) and tumor necrosis factor (from macrophages). Both kill tumor cells; tumor necrosis factor (TNF) also inhibits parasites and viruses.

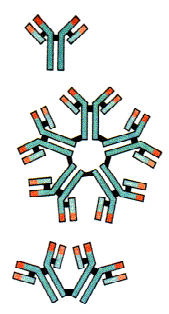

Many cytokines are initially given descriptive names but, as their basic structure is identified, they are renamed as "interleukins"-messengers between leukocytes, or white cells. Interleukin-1, or IL-1, is a product of macrophages (and many other cells) that helps to activate B cells and T cells. IL-2, originally known as T cell growth factor, or TCGF, is produced by antigen-activated T cells and promotes the rapid growth or differentiation of mature T cells and B cells. IL-3 is a T-cell derived member of the family of protein mediators known as colony-stimulating factors (CSF); one of its many functions is to nurture the development of immature precursor cells into a variety of mature blood cells. IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6 help B cells grow and differentiate; IL-4 also affects T cells, macrophages, mast cells, and granulocytes.

A number of cytokines, obtained in quantity through recombinant DNA technology (Genetic Engineering), are now being used-alone, in combination, linked to toxins-in clinical trials for patients with cancers, blood disorders, and immunodeficiency diseases (including AIDS), as well as people receiving bone marrow transplants. Their versatility, however, makes it difficult to predict the full range of their effects.